Witness these bizarre “living fossils” that are still alive today

Science

1. Horseshoe crab

NNehring/iStock

Evolution’s very own Charles Darwin came up with the term “living fossil.” It’s a nickname for any species that doesn’t look very different from how it was millions of years ago. While the species do continuously evolve, they don’t change much because they face little competition for resources. Most living fossils have few living close relatives, because they all died out long ago. Looking at these animals today gives us a little hint of what the world was like long ago.

445 million years ago, the horseshoe crab got to its final form and decided “eh, I’m pretty good like this.” It just had no reason to change drastically, and clearly, something is working since it has lived through all five mass extinctions on Earth. After millions of years of scuttling around in the ocean, however, horseshoe crabs have found their foe: humans.

James St. John/Flickr

Millions of American horseshoe crabs have died for fertilizer and bait use. But in the 1970s, people learned that horseshoe crabs really do have something special. They have a protein in their blue blood that’s essential for testing contamination in medical tools. Now, people collect some of their blood and then release the horseshoe crabs back to the beach.

2. Lamprey

Perhaps the stuff of your nightmares, lamprey have been around much, much longer than humans have been dreaming. Fossils from 360 million years ago show that these vertebrates have changed little through four mass extinctions. They just got really good at being little pests and stuck with it, never looking back as their relatives evolved fins, scales, and jaws.

Jeremy Monroe/Wikimedia Commons

Along with their cousins the hagfish, lampreys don’t have jaws, but that doesn’t stop them from attaching themselves to fish and going full vampire. That’s right, they’re blood-sucking parasites. But don’t worry, they can’t do much harm to humans. In fact, plenty of kings thought they made quite tasty meals.

3. Coelacanth

Not only are coelacanths (seel-a-canths) living fossils, they’re also Lazarus species, meaning they were once thought to be extinct. Scientists figured coelacanths went extinct 65 million years ago with the dinosaurs until they found a live one in 1938. They have some truly unique features, like an electrosensing rostral organ and hinged skull.

Atypeek/iStock

Plus, the coelacanth’s fins are fleshier than the vast majority of fish and they move kind of like a tetrapod’s four legs do. In fact, they’re actually a relative of the same fleshy-finned fish that crawled out of the water to eventually evolve into us. So whenever you look at a dear old coelacanth, think of it as your great, great uncle who’s seen it all.

4. Goblin shark

The goblin shark may look like a derpy Pinocchio at first glance, but once it snatches up its prey, you’ll realize its true attraction. Like “Alien,” the goblin shark’s jaws jump out of their unassuming position and consume the poor fish. It’s truly horrifying and awesome.

Mental Floss

About 120 million years ago, the rare and elusive goblin shark’s ancestors diverged from other shark families. Unfortunately, the goblin shark is the only living member of its family, so it’s pretty distinct from other living sharks. The goblin shark has retained many of the primitive features that other shark lineages have left behind.

5. Tadpole shrimp

There are 250 million-year-old fossils that look a lot like living tadpole shrimp. DNA evidence suggests that they aren’t the same species, despite the physical similarities. However, today’s living tadpole shrimp are still pretty damn old, as one evolved 25 million years ago.

NNehring/iStock

Plenty of scientists resent the term “living fossil” because it makes it sound like the species has simply stopped evolving. This isn’t true; the species all continue evolving and their DNA shows the evidence of millions of years of changing, it just isn’t reflected in their outward appearance. Perhaps they behave differently or are resistant to new diseases, but it’s hard to tell from a fossil.

6. Alligator gar

These huge freshwater fish have remained fairly unchanged for the last 100 million years. They only live in North America now, but they were once found nearly all over the world (except the two poles). The largest gars can be 10 feet long and weigh 300 pounds!

Little St. Simons Island

Gars spend their time drifting around, not doing much, until a smaller fish swims by. Then, with incredible speed, the gar snaps up the fish with its large mouth and sharp teeth. It’s likely that gars have lived for so long because they thrive in less than ideal environments, like oxygen poor waters.

7. Hoatzin

34 million years ago, these dinosaur-like birds lived in Europe and 15 million years ago, they were in Africa. Now, they only live in South America, flapping around the swamps of the Amazon river basin. Curiously, they digest their food kind of like a cow and are the only birds to do this.

Carine06/Flickr

The hoatzin’s most prehistoric feature, though, are the claws on its chicks’ wings. They use them to climb trees, since these birds aren’t all that great at flying. But as the hoatzin grows up, it loses the claws and has to do its best to get around. Hoatzins serve as a colorful reminder that birds are direct descendants of the famous dinosaurs.

8. Vampire squid

Vampyroteuthis infernalis, or the “vampire squid from Hell,” is a charming little cephalopod that lives in the least oxygenated layer of the ocean. Contrary to their name, vampire squids are neither vampire nor squid. They are their own unique kind of cephalopod and eat drifting organic matter (aka marine snow) rather than feasting on the blood of whatever animal strays near.

SciFri/YouTube

While we can’t find a ton of fossil evidence of cephalopods, because they don’t have bones, we do know that the vampire squid’s ancestry goes back 165 million years. It has a mixture of traits from squid and octopodes, so it is evolutionarily distinct.

9. Giant salamander

The Chinese giant salamander’s ancestors differentiated from other amphibians over 170 million years ago. Today, our living giant salamander hasn’t looked very different for a few million years, but now it’s on the edge of extinction due to water pollution, habitat loss, and overfishing. It turns out millions of years of evolution did not prepare it for humans.

Wikimedia Commons

These salamanders can get to be six feet long and spend their time hanging out at the bottom of rivers in China. From there, they can sense prey by picking up on vibrations with special receptors on their skin. The giant salamander opens its mouth wide, sucking in water and the fish swimming in it.

10. Giant freshwater stingray

While the world’s largest living freshwater fish wasn’t properly discovered until the 1980s, it’s been lurking in Southeast Asia’s rivers for millions of years. The problem is it’s so strong and large (up to 16 feet long and 1,300 pounds!) that it destroys nearly any fishing equipment trying to catch it.

Catfish World by Yuri Grisendi/YouTube

Amazingly, these gentle giants don’t mind humans all that much, despite our pollution of their home and fishermen catching them for sport. But if you’re a fish or crab, watch out for the giant blanket of doom smothering you to death after it finds you via your electrical charge (which you have no power to mask).

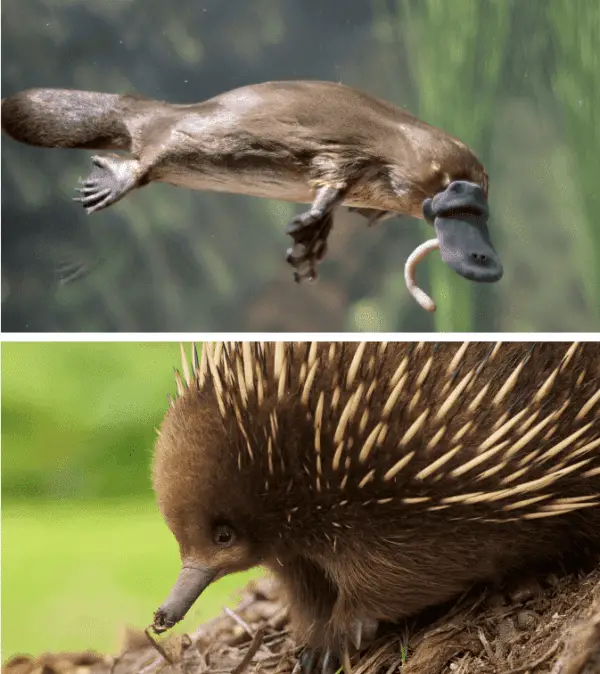

11. Monotremes: platypus and echidna

Platypodes and echidnas hardly look like your run-of-the-mill mammals, but they do belong to a primitive mammal group: the monotremes. They have fur, but they sweat milk and lay eggs, rather than the more newfangled method of giving birth. Plus, platypodes have their very own venom, which is more reptilian than mammalian.

JohnCarnemolla/Byronsdad/iStock

About 166 million years ago, the monotreme ancestor diverged from the reptiles. Then, about 50 million years later, the echidnas and platypodes diverged from each other. It took some time for the two to evolve into what they currently resemble, but these species certainly retained some primitive and weird traits.

12. Nautilus

500 million years ago, nautiluses first started appearing in the oceans. And while there were once over 2,000 different nautilus species swimming around, now we have six that look fairly unchanged from their first ancestors. These odd floating spirals are actually related to octopodes, squids, and cuttlefish, as they are all cephalopods.

glucosala/GoodFreePhotos

But despite their primitive looks, nautiluses are harboring their own mysterious secrets. They have the capacity for long-term memory, even though they don’t have the brain structure that does this for other cephalopods. Plus, their spiraled shell contains multiple compartments, which they maneuver water through to propel themselves around the ocean.

13. Amami rabbit

About 10 or 20 million years ago, the Amami rabbit arrived at two islands south of mainland Japan: Amami and Tokuno. There were no other rabbits on the islands and few predators, so the Amami rabbit just kept its primitive looks. Unlike modern rabbits, the Amami rabbit has short ears, small eyes, and long curved claws.

dinets/YouTube

The Amami rabbit is more Bunnicula than Peter Rabbit since it’s completely nocturnal. Once every night or so, a mother Amami rabbit visits the burrow she enclosed her baby in. She only has one baby at a time, unlike most rabbits, which may be part of the reason these rabbits are endangered. That, combined with the fact that people released Javan mongooses onto the islands to kill poisonous snakes. The mongooses ate the rabbits instead.

14. Frilled shark

The delightful frilled shark may look like an alien or monster from a B-horror movie, but it’s been living on Earth much longer than you have. Physically, it’s changed little since its relatives were swimming in the dark 100 million years ago. Shark teeth are often the only part fossilized, so it’s lucky these guys have 300 of them.

Getty Images

If it makes you feel better, these primitive sharks are rare to see because they live around 3,000 feet deep in the ocean. They are occasionally caught in fishing nets, but it may be sickness making the odd individual swim in shallower waters.

15. Monito del monte

The “monkey of the mountains” is actually a South American marsupial and the only living member of its otherwise long dead order, Microbiotheria. It hasn’t changed much in the last 46 million years, keeping its mousy physique as it climbs large bamboo stems. Curiously, monito del montes hibernate through the winter, which most marsupials don’t do.

Wikimedia Commons

Next Christmas, think of this little marsupial as you kiss someone under the mistletoe because it eats mistletoe fruit and pops out the seeds all over the forest. In fact, one particular species of mistletoe only germinates after passing through the digestive tract of a monito del monte.

16. Gharial

Crocodilians have long been called living fossils and put in illustrations or museum scenes alongside dinosaurs. Well, they have been around a long time, but there have been a great many different kinds of crocodilians and they’ve gone on their own evolutionary journey. Once upon a time, there were crocodilians climbing trees and sprinting.

Wikimedia Commons

The gharial looks a lot like a fossil from 70 million years ago, but DNA evidence suggests they’re actually not related. Instead, they independently evolved similar long, toothy snouts. The gharials actually diverged from other crocodilians about 30 million years ago, so they’re still really old, just not dinosaur old. Now, they’re critically endangered.

17. Sumatran rhino

The critically endangered Sumatran rhino has been around for at least a million years, since it actually hit its peak population 950,000 years ago. Back then, there were about 57,800 adult Sumatran rhinos running around. 9,000 years later, that number dropped to 700.

Wikimedia Commons

Climate change at the end of the last Ice Age nearly wiped them out. Since then, the rhino population has never recovered. Humans came along and started hunting them and destroying their habitat. Now, there are about 250 mature adults left. Amazingly, they are only the second most endangered rhino species. There are only about 50 adult Javan rhinos left.

18. Tuatara

Tuataras may look like lizards, but the two reptiles diverged 240 million years ago onto different evolution tracks. While the tuatara’s ancestor went on to become a diverse array of species, all but the tuatara died out. This cheeky reptile managed to spend the last 200 million years living in New Zealand with few changes to its body and diet.

Bernard Spragg/Flickr

Unlike most other reptiles, tuataras prefer cooler temperatures and hibernate during the winter. Plus, they have a third eye on top of their heads that’s covered up by scales after about four or six months (it might absorb ultraviolet light and help with circadian cycles). Invasive rats have pushed wild tuataras to only live on 32 islands off the shore of mainland New Zealand.

19. Laotian rock rat

The Laotian rock rat was discovered by scientists in a meat market in Laos in 1996, where it was being sold as food. When the researchers compared it to living species, nothing was even similar to it. But once they looked further back, into the fossil record, they realized it was a species that seemingly disappeared 11 million years ago.

Wikimedia Commons

Yup, the Laotian rock rat is another Lazarus species. It originally appeared 32.5 million years ago but was thought to be long dead in modern times. Luckily, we live on an Earth with a healthy population of weird squirrel/rat creatures. If we didn’t, who knows where we’d be.

20. Red panda

About 5 million years ago the unequivocally adorable red pandas actually lived in North America. Now, the endangered species only lives in a slim area of mountainous forest that stretches across China, India, Nepal, Myanmar, and Bhutan. They have no close relatives and are only distantly related to giant pandas.

Freder/iStock

Red pandas spend most of their time climbing and jumping through trees. While their red coats and white markings stand out to us, the colors actually act as camouflage. Red moss and white lichen grow on tree trunks, hiding them from snow leopards and other predators. Like their giant cousins, red pandas eat mostly bamboo, but they do vary it up with eggs and small animals.

21. Elephant shrew

About 20 million years ago, elephant shrews first appeared in the fossil record. They all live in Africa and are not actual shrews, but more closely related to elephants. There are 19 species of elephant shrew, but those in the genus Rhynchocyon particularly resemble their ancestors of old.

Wikimedia Commons

All elephant shrews belong to the order Macroscelidea, which essentially means “large thighs” in Greek. Now, who wouldn’t want to be named Large Thighs? Most elephant shrews are monogamous: they control territory with their partner and make several nests in the area to shelter in. But the two aren’t very romantic, barely interacting unless to mate.

22. Opossum

About 50 million years ago, an animal that looked a lot like modern opossums lived in North America. If you looked at one of these ancient marsupials and a modern opossum, it’d be like a game of spot the differences. Behaviorally, the prehistoric opossum spent less time in trees and more time on the ground.

stanley45/iStock

But that ancient opossum didn’t stay in North America, it went south and then about three million years ago, the modern Virginia opossum crossed Panama back to North America. Whenever an opossum is seriously threatened, they involuntarily fall into a sort of coma and emit a terrible smell. Hours later, the opossum awakens, having played dead long enough to avoid being eaten.

23. Chevrotain

Perhaps a mouse and deer canoodled 20 million years ago to make chevrotains, the tiny hoofed animals running around Southeast Asia (and parts of Africa). Alright, that’s probably not what happened, but modern chevrotains still look like their ancestors from that time period.

aee_werawan

Chevrotains are nocturnal, mostly solitary, and about the size of a rabbit. Some of them swim very well and can even hold their breath underwater for up to four minutes. They eat a lot of fruit and the males have little fangs, making them look like adorable vampires. At least one species of chevrotain (aka mouse deer) is endangered.

24. Alligator snapping turtle

Once thought to be only one species, scientists determined that alligator snapping turtles are actually three distinct species. They diverged from each other somewhere between 3.2 and 13.4 million years ago, thus embarking on their own evolutionary journeys to their modern selves. While they all look alike, their DNA contains differences and they don’t all live in the same areas.

thomasmales/iStock

The alligator snapping turtle’s close relative, the common snapping turtles, have also been around for a long time. The members of their family remain relatively unchanged for the last 90 million years. Snapping turtles live in freshwater in North America.

25. Solenodon

Solenodons are part of a very peculiar and exclusive club: mammals that produce venom. Sure they look nondescript, but you’d do best to avoid their snake-like bite. The two living species of solenodon split apart 25 million years ago, but solenodons have looked about the same since 76 million years ago.

Wikimedia Commons

Along with their incredibly flexible snouts and goat-like odor, solenodons live in the Caribbean. Unfortunately, these little guys are endangered. It’s probably because when faced with an invasive predator, they sit still and hide their heads in a “you can’t see me if I can’t see you” logic, rather than actually running away.

26. Aardvark

Looking a little like a pig and a bit like an anteater, the aardvark’s closest living relative is actually the elephant. That might give you a hint as to how evolutionarily distinct these weird mammals are. About 55 million years ago they looked nearly the same as they do now.

mason01/iStock

To avoid Africa’s hot afternoons, aardvarks sleep during the day and dig up food all night long. In the process of digging into a sweet termite mound, an aardvark closes its nostrils to keep dust and insects out because there are few things worse than a bug up your nose.

27. Sandhill crane

Sandhill cranes migrate across much of North America each year and they may have been doing so for the last 2.5 million years, which is the oldest sandhill crane fossil scientists have found. These birds are moving around from a young age: just eight hours after hatching, they can leave the nest and start swimming.

Becky Matsubara/Flickr

Between the ages of two and seven, the cranes begin breeding. To attract a life-long mate, sandhill cranes court their would-be lover via an energetic, but graceful dance. The pair will stay together all year for the next two decades or so (the oldest sandhill crane on record was actually 36 years old).

28. “Ant from Mars”

Martialis heureka’s name means “Ant from Mars,” but unfortunately, no, it was not found on Mars. It lives underground in the Amazon rainforest and has no eyes because its subterranean home is too dark to need them. This little pale species was only discovered in 2003 and officially named in 2008, but it’s been around obviously much longer than that.

California Academy of Sciences/Wikimedia Commons

All ants can trace their lineage back to 120 million years ago when their ancestor diverged from the wasps’ ancestor, but this particular ant evolved its traits not long after that split. To this ancient species, we probably seem like we’re from Mars.

29. Pelican

Fossils suggest that pelicans haven’t changed much in the last 30 million years, as their distinctive beak (plus skull and neck bones) was found preserved in southeastern France. However, back then, the pelican wasn’t using its beak to save clownfish from certain doom in the hands of small children.

tracielouise/iStock

There are four species of pelican alive today, and while they have different colored feathers, they all have the same giant pelican beak. The beak allows pelicans to scoop up prey from the water and then spit out the water before eating the food. Plus, it’s the longest beak of any living bird.

30. Pygmy right whale

Scientists thought this whale family went extinct two million years ago, but once they studied the DNA of the elusive pygmy right whale, they realized it was the last living member of the Cetotheriidae family. This family had emerged 15 million years ago and once swam all over Earth.

Science Direct

Pygmy right whales have baleen (filtering brushes) instead of teeth. They’re the smallest of all baleen whales at 21 feet long and live in the southern hemisphere’s oceans, far from land. Since they are so hard to find, little is known about them, but it seems they evolved nine million years ago.